Amanullah Mojadidi

(b. 1971, Jacksonville, USA, lives and works in Paris, France)

Untitled Garden #1, 2015-2016

Neon, wood, stone and grass

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist. Dhaka Art Summit and Samdani Art Foundation.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Untitled Garden #1 by Amanullah Mojadidi opens up a space to think about the role misunderstandings play in shaping history and the way we view our place in the world. Neon Katakana Japanese characters in this garden spell the word Mu, referring to a state of “nothingness” or “nonbeing” in Zen Buddhism. Mu, however, is also the name of what several pseudoscientists believed was the lost continent and civilisation of Mu, a white race civilisation that fell into the ocean but whose descendants became the great early cultures around the world, including in India. The neon crown in the garden refers to a sacred symbol of this lost Kingdom of Mu, representing "The Lands of the West." In this work, the Japanese definition of Mu is a place with an absence of desire; the second symbol of Mu illustrates what happens with the human desire to explain what they cannot understand.

Mojadidi’s Zen Garden explores the hidden dangers of how Eurocentric institutions present themselves as “discoverers” of art from conflicted/developing countries, and creates parallels between the colonial anthropologist discovering the noble savage in exotic lands and the Western curator discovering the noble artist in equally exotic locales. Mojadidi takes a sarcastic approach toward the Afghan and American culture that he comes from, and stereotypes surrounding identity and the capitalism around conflict. “We are all at conflict,” shares Mojadidi, “Whether with others or ourselves, with our own ideas, thoughts, desires, history, present, future. We are all at conflict as we try and navigate ourselves through a life we understand only through our experiences, through our confrontation both internal and external with social, political, cultural, and personal strife.”

Ayesha Sultana

(b. 1985, Jessore, Bangladesh lives and works in, Dhaka, Bangladesh)

A Space Between Things, 2015-2016

Iron, plaster, wire mesh, glass, glue, paint, concrete, aluminium, copper, wood, brass and fabric

Commissioned by the Samdani Art Foundation. Courtesy of the artist, Samdani Art Foundation and Experimenter

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Ayesha Sultana’s newly commissioned solo project, A Space Between Things, is an ongoing exploration referencing the theme of landscape that threads much of her practice. Sultana works in intimate proximity to the material around her, sensitively reconfiguring it and adding to the potential energy that lies in the space between function and dysfunction. The artist playfully sculpts material culled from found and reclaimed objects, revealing the transitory and fragile nature of our natural and built surroundings, signifying and revealing distance, movement and space. She draws the viewer into the curiosity she has for the process of making and reconfiguring, and creates an enhanced sense of suspense relating to the possible changes the work could undergo over time through the hand of the artist or through the hands of time. Key ideas of transience, contact, balance, weight, and collapse manifest in gestural arrangements that Sultana creates with materials such as wood, metal, mylar, fabric, plaster, stone and glass.

Sultana is interested in the duality and coexistence of the material and the immaterial. She strives to free her work from its very rooted and specific Bangladeshi context into a fluid and wide-ranging space, where the work can be set loose within its own parameters. For example, a vertical metal form could vaguely refer to early inspiration of viewing classical architectural structures such as columns and ancient obelisks. The individual works can maintain an interest in a nondescript condition even as particular references are apparent. This is a project that needs to be navigated spatially, and experienced in relation to the scale of the body, a space where transformation and understanding happen not from the description, but rather from experience, which the artist creates through the convergence of will and chance as she intervenes with found and made objects using time as a malleable medium. It is a celebration of what is possible when you allow experience to draw your mind to conclusions, rather than relying on the human tendency to come to a situation with preconceived definitions.

Through sound, drawing, sculpture and photography, Jessore-born and Dhaka-based artist Ayesha Sultana considers the poetics of space and the relationship between material and process in notions of making. Within the context of drawing, her practice in the recent past has been an investigation into the rudiments of form through architectural constructions, often derivative of the landscape and attempting to peer into what is out of view. Counter tendencies of movement and stability are also evident as an attempt to generate emptiness by filling up the surface. Through other elemental gestures and implications of plotting, measuring and erasure, merging and filling-in, Sultana makes an otherwise fractured image. Sultana was the winner of the 2014 Samdani Art Award and was featured as one of ArtReview’s “Future Greats” in 2015. She is a member of the Britto Arts Trust and a graduate of Beaconhouse National University in Lahore.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

(b. 1979, London, UK, lives and works in London, UK)

(featuring drawings by Kavinda Silva & Prageeth Manohansa)

When Platitude Become Form, 2016

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation. Courtesy of the artist and the Samdani Art Foundation. Photographer: Jenni Carter

Christopher Kulendran Thomas is an artist who manipulates the processes through which art is distributed. He takes as his materials some of the cultural consequences of the economic liberalisation that followed the end of Sri Lanka’s 25-year civil war in 2009. Through what is now called terrorism and genocide, this civil war was waged between Hindu Tamil separatists (popularly known as Tamil Tigers) who wanted to establish a homeland called Tamil Eelam in the Northeast of the Island and the Buddhist Sinhalese Majority Sri Lankan government. ‘Peacetime’allows for tourism and aspirations of a comfortable future to flourish, and art galleries and design shops have been opening over the past six years and the cultural industries are growing with fashion weeks, biennales, and other festivals.

Thomas purchases artworks from the island’s contemporary art scene and reconfigures or reframes them for international circulation. Incorporating these original artworks into his own compositions, Thomas exploits the gap between what's considered contemporary in two different art markets and the gap between his family's own origins and his current context as a London based artist with access to the global networks of the contemporary art world. Taking this idea a step further, the artist is launching a brand called New Eelam that imagines the future of citizenship in an age of technologically accelerated globalisation. It is a speculative proposal based on a reinterpretation of the political philosophies of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. How would history have unfolded if the Tigers had manipulated the mechanics of global capital better than their enemy? This proximal sci-fi proposition speculates on how a nation might be reimagined without a territory and on how a corporation might be constituted as a state.

Dayanita Singh

(b.1961, New Delhi)

Museum of Chance, 2014

Book object, edition of 352

Courtesy of the artist. Photographer: Noor Photoface

'While I was in London I dreamed that I was on a boat on the Thames, which took me to the Anandmayee Ma ashram in Varanasi. I climbed the stairs and found I had entered the hotel in Devigarh. At a certain time I tried to leave the fort but could not find a door. Finally I climbed out through a window and I was in the moss garden in Kyoto."

Dayanita Singh's Musuem of Chance is a book about how life unfolds, and asks to be recorded and edited, along and off the axis of time. The inscrutably woven photographic sequence of Singh's Go Away Closer has now grown into a labyrinth of connections and correspondences. The thread through this novel like web of happenings is that elusive entity called Chance. It is Chance that seems to disperse as well as gather fragments or clusters of experience, creating a form of simultaneity that is realised in the idea and matter of the book, with its interlaced or parallel timeless and patterns of recurrence and return.

Haroon Mirza

(b. 1977, London)

The National Apavilion of Then and Now, 2011

LED, foam and sound

Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London. Photographer: Noor Photoface

Haroon Mirza asks us to reconsider the perceptual distinctions between noise, sound and music, and draws into question the categorisation of cultural forms. The National Apavilion of Then and Now , 2011 lined with dark grey sound-insulating pyramidal foam, is an anechoic chamber in which neither light nor sounds is reflected. At the centre, hanging from the ceiling, there is a ring of white LED lights, reminiscent of nimbus effects. After a period of total darkness, the LEDs grow progressively brighter, accompanied by an also ever more enhancing buzzing sound, which abruptly stop, plunging the room in darkness once more, until the cycle starts again. The work evokes intense physical experiences of the perception of sound, light, space and time that seem to echo across the past and future of the universe. The light in this work is reminiscent of a halo, a form used to connote being outside or above the physical human realm.

Like many of the other works in the exhibition, Mirza's work rejects recording or representation that limits its complexity; it must be physically felt to be experienced. The work draws parallels between the electrical wiring of circuits and the body; Mirza proposes a third space between seeing and hearing. where imperceptible waves of sound and light draw attention to the role of perception in shaping our view of reality and how we access knowledge.

Lynda Benglis

(b. 1941, Lake Charles, USA, lives and works in Santa Fe, USA, New York, USA, Kastelorizo, Greece, and Ahmedabad, India)

Wire, Kozo paper, phosphorescent pigments and acrylic

Courtesy of the artist and VAGA, New Work. Photographer: Jenni Carter

Over the past fifty years, Lynda Benglis has divided her time between studios in New York and Santa Fe in the United States of America, Ahmedabad in India and Kastelorizo in Greece, with each diverse location having subtle, yet discernible, influences on her work. Reflecting on her over thirty year experience in India, Benglis shares that she was always exploring “how form is discovered through texture, through movement; form is movement… I felt very much at home [in India]… because there is a sense of the “spirit” of natural form and inspired texture, and it occurs in art, architecture, music and dance.” Benglis is known for her radical re-visioning of painting and sculpture in her innovative and prolific practice, seeking a more sensuous kind of surface.

Benglis explores how what we see influences our body, a concept known as “proprioception”. “We experience something in our bodies that is proprioceptic; we experience it in our whole body – you feel what you see and you are ‘charged.’ It’s an exchange of energy.”2 Benglis presents seven new cast paper sculptures created especially for the Dhaka Art Summit, reference her wax and glitter works from the 1960s and 1970s. These handmade paper forms are sculpted over chicken wire, a common element in the visual landscape of South Asia, with glimpses of colour and sparkle that are informed by the artist’s formative years in Louisiana and her life in India: each with their rich festival cultures, such as Mardi Gras and Holi. Chicken wire has allowed Benglis to co-opt the grid harnessed by modernism and minimalism and transform it into a fluid and amorphous form that is fully her own.

Walking further into the project, seven similar forms emerge from the dark in a second room, glowing from Benglis’s painterly work with phosphorescent materials. Through these fourteen works, Benglis creates a physical moment in a space, and writer Marina Cashdan draws connections between the phosphorescent work and the colours that people often experience in deep meditation, connecting physical movements of breath that become visual forms inside the body. Lynda Benglis is recognised as one of the most important living North-American artists. A pioneer of a form of abstraction in which each work is the result of materials in action — poured latex and foam, cinched metal, dripped wax — Benglis has created sculptures that eschew minimalist reserve in favour of bold colours, sensual lines, and lyrical references to the human body. But her invention of new forms with unorthodox techniques also displays a reverence for cultural references tracing back to antiquity.

Benglis has received numerous awards and her works are held in leading institutional collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Tate, London and the Guggenheim, New York and she has recently exhibited in major career survey exhibitions at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; the New Museum, New York; Storm King, New York and the Hepworth Wakefield, UK.

Munem Wasif

(b. 1983, Comilla lives and works in Dhaka, Bangladesh)

Land of the Undefined Territory, 2015

26 Digital Photographs and three channel HD black and white video with stereo sound, 20min 16 sec

Project debut at the Dhaka Art Summit 2016 with partial production support from Samdani Art Foundation. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit and Samdani Art Foundation.

Photo credit: Jenni Carter

Munem Wasif’s haunting series of photographs and three-channel video of an undefined land elucidates the dialectic relationship between a land and its identity, an identity at risk given the relatively new concept of the nation state and of the environmental effects of man’s “progress” post the industrial revolution. Situated on the edge of a blurred boundary of Bangladesh and India, the mundane, almost extra-terrestrial land hides human interaction with its surface and exposes ever-changing curves with Wasif’s repetitive frames. It seems that frames rarely move from each other, slowing down time and motion and blurring the character of a land, disassociating it from its political and geographical identity. This Solo Project, entitled Land of the Undefined Territory questions the identity of a land that is tied to a specific political and geographic context, but which could also be anywhere, as Wasif displaces the viewer from space and time. Wasif’s dispassionate and systematic approach in this series mimics that of an investigation, topographic study, geological survey or a mere aesthetic query, however his technique of using look-alike frames and ambient sounds overcomes the optical unconscious of the camera and evokes elusive feelings and absurd sensitivity in the viewer.

The chosen area of land in this series is a mere observer of nearly a hundred years of land disputes, which saw colonization, 1947’s divide of the Indian subcontinent and mass-migration with Partition, and 1971’s liberation war of Bangladesh which created the current border tension with the neighbouring country, India. Absence of any profound identity for its existence never diminishes its presence, and its body carries the wound of aggressive industrial acts, such as stone collection and crushing. This land belongs to no one, and is thus exploitable by anyone motivated to avail of the land’s unlikely riches. As hills and mountains are cut away to mine the material needed to build Bangladesh’s roads, the communities who have lived on the land for thousands of years become alien to it, as they can no longer identify their community by natural markers. In his video, Wasif captures suspended motions by not moving the camera and by recording predominantly still objects, enhancing the sense of timeless limbo that has now come to define this land, and potentially elsewhere in the future.

Mustafa Zaman

(b. 1968, lives and works in Dhaka, Bangladesh)

Lost Memory Eternalised, 2015-2016

Digital Print on paper

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit, Samdani Art Foundation and Exhibit320, New Delhi.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Mustafa Zaman’s Solo Project Lost Memory Eternalised is an unauthorised retelling of the past, revealed after readjusting the lens to the events in the lives of human beings on Earth – where the human condition(s) shaped by history leaves us in awe of the events that make up our experiential domains, giving rise to moments of epiphany and other forms of awakening, which cannot be explained away.

Images can be read in the context of their time and place and also in their relationship to eternity. The artist emphasises the latter relationship by overlaying found images with honey, enhancing the sense of transcendence/timelessness inherent in each image, but leaving a symbolic residue of dead ants that speaks to a collective disillusionment, citing a sense of loss which often colours our perception of time. With the intrusion of an additional substance (i.e. honey with dead ants), the historicity of the source images is destabilized. They now invite touching and enforce a renewal of vision. Each image serves as a cue to a larger universe or existential realm, consistently changing under the forces of creation and destruction. Each image primes us to look at how individual desire, and resulting disillusionment, shape both individual and collective history.

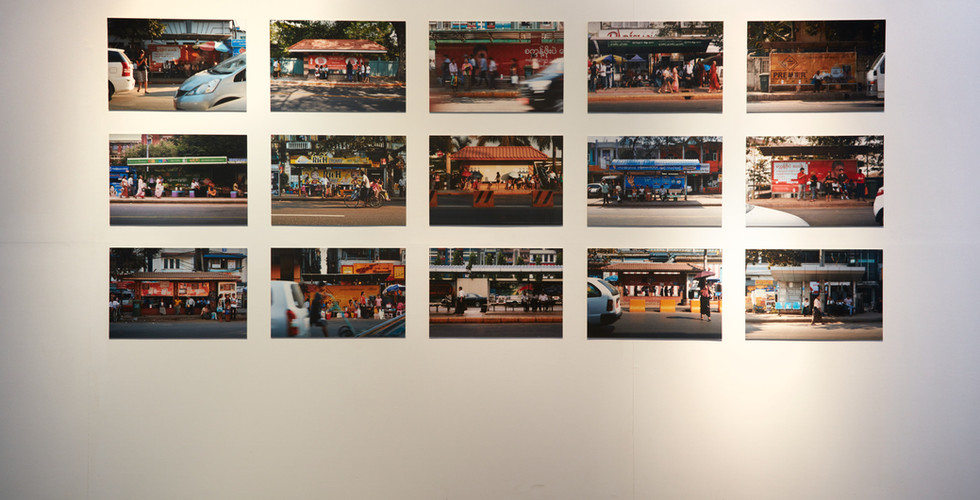

Po Po

(b. 1957, Pathien, Myanmar, lives and works in Yangon, Myanmar)

VIP Project (Dhaka) 2014-2015

Photographs and video

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit and Samdani Art Foundation.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

The self-taught pioneer in Burmese contemporary art, Po Po describes his photography not as a visual record, but as a means to reflect his thoughts regarding political, social and cultural concerns. In 2010, Po Po created his first “VIP Project” in Yangon, placing VIP signs in public bus stops across the city. South Asia has a deeply entrenched “VIP Culture” where certain individuals are given preferential treatment as “Very Important People” – even in the public sector with special entrances in airports, parking spaces, and other basic facets of daily civic life. Standing across the street from bus stops, Po Po took a series of photographs and videos documenting the reactions of people to the signs —in nearly all cases, the commuters saw the sign as more important than them, yielding their seats to the signs, demonstrating their thoughts of their place in society as not as important as anonymous and invisible others who may or may not arrive.

Politics play a key role in shaping one’s view of their place in the world. Five years after his first VIP project, Po Po created the second chapter in Dhaka, a city with a similar social VIP culture and historically under the same British rule as Yangon, but with a different political history of over forty years of democracy as opposed to Myanmar’s over five decades of military rule. While the reactions of the public seem similar in the video and photographic documentation across Yangon and Dhaka, the Bangladesh political scenario opened up the possibility for a few members of the public to think of Po Po’s intervention as a joke. This reaction never occurred in the Myanmar intervention, as choice of interpretation of public signage was not an option.

Prabhavathi Meppayil

(b. 1965, lives and works in Bangalore, India)

Dp/Sixteen/Part One,2015-2016

Wood, copper and gesso

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation. Courtesy of the artist, Samdani Art Foundation and PACE, London

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Entering the central hall of the Dhaka Art Summit, Prabhavathi Meppayil unsettles the viewer by turning the room upside down, creating an immersive installation which displaces the negative space of the coffered ceiling outside the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy and placing it inside the floor of the building. Meppayil’s art practice draws on traditional cra and values the truth of materials and tools as well as simple forms, colours and shapes. Coffered ceilings are an ancient and universal element of architecture. In her installation dp sixteen (2015-2016) Meppayil creates movement between the floor and ceiling, outside and inside. She creates a subtle phenomenological experience of an architecture connected to an infinite grid of cubes. In his analysis of Meppayil’s work, Benjamin Buchloh points out that grids are possibly the most basic principle of modernist abstraction, and also panels for tantric meditation. He continues that “Meppayil’s paintings seem to be driven by a latent desire to leave behind the parameters of pictorial space and its supporting surfaces, reaching for an ultimate sublimation of the painterly rectangle in a numinous architectural space.”

Meppayil transforms her “painterly rectangles” through meditatively applying white gesso, a material used in most of her work since 2009 that is traditionally used to prime wooden surfaces for later layers of paint. Through her choice of materials, the artist extends painting into the space of architecture, where wood, grids, layers, wiring, and primed surfaces create environments for us to inhabit. Her intervention simultaneously creates order and disorder in the exhibition space, and reminds the viewer to consider the seen and unseen elements creating our sense of being in the world.

Sandeep Mukherjee

(b. 1964, Pune, India, lives and works in Los Angeles, USA)

The Sky Remains, 2015-2016

14 panels of acrylic ink and embossed drawing on duralene (wall) 1000 panels of acrylic ink and carved drawing on plywood (floor)

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit, Samdani Art Foundation and Project 88, Mumbai.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Possession and dispossession, displacement and debt—it seems that the stories that condition our present are inextricably born out of the stories that conditioned our past. The first of four special issues of South as a State of Mind, temporarily reconfigured as the documenta 14 journal, examines forms and figures of displacement and dispossession, and the modes of resistance—aesthetic, political, literary, biological—found within them. In essays, both literary and visual, as well as poems, speeches, diaries, conversations, and specially commissioned artist projects, the first issue of the d14 South considers dispossession as a historical and contemporary condition along with its connections to archaeology and the city, coloniality and performativity, debt and imperialism, provenance and repatriation, feminism and protest.

To launch the inaugural issue of the d14 South, documenta 14 has organized a series of public events—in Athens, Kassel, Berlin, Dhaka, and Kolkata—that bring the disparate voices of the journal, as well as those outside of it, into conversation in cities across the world. This February, South goes to Bangladesh and India for two launch events. The first will be held in Dhaka on February 6, the second in Kolkata on February 10.

For the Dhaka launch at the Dhaka Art Summit, in the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, documenta 14 Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk and Editor-in-Chief of Publications Quinn Latimer will present the first issue of the documenta 14 South as a State of Mind, reading from and expanding on its diverse explorations of both contemporary and historical forms of displacement and dispossession. In addition, they will elaborate on forthcoming issues of the d14 South, which are variously devoted to ideas of language and ecology, post-colonialism and neoclassicism, and the rich relationship among pedagogical, performative, and political processes.

South as a State of Mind is a magazine founded by Marina Fokidis in Athens in 2012. Beginning in 2015, the magazine temporarily became the documenta 14 journal and will publish four semiannual special issues until the opening of the exhibition in Athens and Kassel in 2017. These special issues are edited by Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk. The documenta 14 South is conceived as a medium for research, criticism, art, and literature that parallels the years of work on the d14 exhibition overall, one that helps define and frame its concerns and aims. As such, the journal is a manifestation of documenta 14 rather than a discursive lens through which to merely presage the topics to be addressed in the eventual exhibition. Writing and publishing, in all their forms, are an integral part of documenta 14, and the journal heralds that process.

Through this collaboration with documenta 14, The Seagull Foundation for the Arts continues its multi-faceted role in actively supporting and disseminating arts and culture publishing, as well as critical theory. This launch event is hosted at Harrington Street Arts Centre, where Seagull has previously organized several events and exhibitions, including a forthcoming solo show by K. G. Subramanyan, titled Sketches, Scribbles, Drawings.

Shakuntala Kulkarni

(b.1950, Dharwad)

Of Body, Armour and Cages, 2012-2015

Cane and four channel video with sound (Julus)

Courtesy of the artist and Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai. Photo credit: Jenni Carter and Noor Photoface

Walking into Shakuntala Kulkarni’s solo project, the viewer is confronted with an army of five figures sculpted from traditional cane weaving practices from the eastern part of South Asia. On closer inspection, references of Xi An Terracotta Warriors, Bollywood superheroes, hairstyles from Roman and Hellenic times, and Viking warrior plaits harness the imagination away from any one particular time and place to address the timeless issue of how to exist as an individual in a world that encroaches on individual rights, especially the individual rights of a women. These sculptures come to life through kulkarni’s newest work Julus, an immersive four channel video work where a procession of the multiple selves of the artist storm the space and demand attention, freedom, and respect.

Shakuntala Kulkarni is a Bombay based multidisciplinary artist and activist whose work is primarily concerned with the plights of urban women who are often held back due to patriarchal expectations. By placing her sculptures over her body, the artist dictates where the viewer’s gaze will lie, reclaiming power away from the viewer and allowing herself to be looked at on her own terms. “The bodied self can be insulted, subjugated, incarcerated, curbed by religious decree, dictatorial whim or popular sentiment. It can be deprived of the rights of mobility and expression… An armoured body can extend its capabilities through the mailed fist, the spiked helmet, the radiation-proof bodysuit, or heightened fight/flight reflexes. But the body pays for this protection with its freedom. The armour becomes a cage. The self becomes prosthetic: protected by, yet trapped within, an exoskeleton,” writes Ranjit Hoskote. This tension between the power and the vulnerability of the body creates a powerful artistic statement, as does the social commentary when the artist takes her armour out into public space in india. If she can choose to wear a dress of velvet, why can she not choose to wear a dress.

Shumon Ahmed

(b. 1977, lives and works in Dhaka, Bangladesh)

Land of the Free, 2009-2016

Video (looped), photographic print on archival paer, 30 sec

VR goggles with extreme isolation headphones with sound and video, 1 min 30 sec

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit, Samdani Art Foundation and Project 88, Mumbai.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Shumon Ahmed’s Solo Project builds upon a prior body of work, Land of the Free, which immerses the viewer into the delicate continuum between sanity and madness that shapes an individual from within. “Reason, or the ratio of all that we have already known,” wrote William Blake in 1788, “is not the same that it shall be when we know more.” This ratio is delicate, and our minds naturally fight to keep equilibrium that anchors us to a sense of reality.

Mubarak Hussain Bin Abul Hashem, or ‘enemy combatant number 151’, was flown back home to Dhaka in 2006 after having endured five years of torture and imprisonment at Guantánamo Bay. Through processes of humiliation, sensory overload and deprivation, Mubarak’s sense of self was broken down in an attempt to harvest information against his will, to sever his mind from reason. Ahmed’s project thrusts visitors into the grey spaces of the mind through harnessing torture techniques within the artworks, employing stereoscopic goggles, headphones, and powerful imagery and sound to transform his photographs into a physical experience for the viewer. This project investigates trauma that leads to insanity, and reveals processes designed to crack the human soul. It draws inspiration from W.J.T. Mitchell’s work on “Seeing Madness,” as Ahmed’s images draw us into Mubarak’s compromised senses. The idea of the ‘Land of the Free’ takes on a new meaning as viewers confront an aged Mubarak whose physical body finally finds freedom, but not without permanent mental fog and a lingering sense of displacement resulting from five long years of trauma.

Simryn Gill

(b. 1959, Singapore, lives and works in Sydney, Australia and Port Dickson, Malaysia)

Ground, 2016

Thread and Paper

Commissioned and produced by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Dhaka Art Summit, Samdani Art Foundation and Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai.

Photographer: Jenni Carter

Simryn Gill makes poetic links between art, paper, books, and nature in her work; all begin with seeds that grow roots. The idea of roots can be abstracted into square roots in mathematics, roots of language, roots of belonging, and seeds to seeding ideas and to the ability to traverse manmade ideas of border. Gill shares, “for me, plants and the plant work offer a powerful way to think about where we find ourselves now and how we grow into and adapt to our sense of place. There is a line from one of [William] Blake's poems in his Songs of Innocence, ‘and we are put on earth a little space'. That little space is not a bit of geography anymore, but it seems to be literally the physical room we occupy with our bodies as we carry ourselves around trying to make sense of how to stake claims on constantly shiing grounds.” Reflecting on the slippery concept of place years later, Gill elaborated that “I came to understand place as a verb rather than a noun, which exists in our doings: walking, taking, living.”

In an unpublished text in 2012, she continues this train of thought, “If you are empty, nothing, you only exist through the things around you, and if these things shift in their qualities and values, in relation to you, each other and other things, then the sense of self is always moving too. And the other way around: when I am the vector that is moving, then the things around me change, and my relationship to them too, how I do or don't connect, comprehend, sympathise. These are the un-static beacons we use to navigate through daily being.”

Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu

(b. 1975, Ywalut, Myanmar, b. 1977, Yangon, Myanmar, live and work in Yangon, Myanmar)

Ipso Facto, 2011-2013

6 paintings (emulsion on linen, net, 275 x 580cm each) and video (colour, with

sound, 20 min. 54 sec.), approximately 7 x 16 x 3m overall.

Work realised within the framework of the exhibition at the Atelier Hermès thanks to the support of the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès. Courtesy of the artists. Photographer: Noor Photoface

In traditional theatre in Myanmar, a simple twig on stage signified a forest scene; this idea was so recognisable that it could not possibly suggest anything else. Myanmar is rich with natural resources, and as the country was closed off to the rest of the world for over fifty years, there is little documentation of the vast changes in the natural landscape that occurred during this time as different parties in favour with the government devastated the land and amassed great riches. In their solo project Ipso Facto, Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu collaborated with traditional theatre backdrop makers (with Tun Win Aung as the painter) to set the stage to discuss the dramatic environmental changes that have dislocated national identity from the land. For example, the natural mud volcanoes that once existed both physically and as part of local myth are now almost entirely dry, and the next generation will no longer be able to relate their imaginations to the landscape. The UN has recognised Myanmar as one of the countries with the highest rate of forest loss on Earth (the total forest coverage area dropped from 51% in 2005 to 24% in 2008), and soon the next generation might not recognise the dramaturgical stick as the site of a lush forest. In theatre and in domestic life, curtains suggest a portal to another space. The world of theatre uses artifice to show the real, and excess to accentuates parts of reality that might otherwise be overlooked.

Here, the viewer walks through a jungle of six backdrop paintings while confronting a seven channel video work that accentuating the sense of loss of the thought of losing one’s landscape.

In addition to working individually as visual artists, this Yangon-based husband and wife duo Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu work collaboratively in a range of media including painting, video, performance, and installation. In 2009, the artists began the multicomponent work 1000 Pieces (of White), gathering and producing objects and images to assemble a portrait of their shared life. Their work often reflects politically inflected experiences and through their Museum Project, they collaborate with artists all over Myanmar and exhibit their work in rural contexts, imagining possibilities of what a museum in Myanmar might be. While Tun Win Aung’s practice frequently focuses on local histories and environments, Wah Nu is inspired by her interest in psychological states. They have showcased their work in international venues such as the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, the Singapore Art Museum and Guggenheim, as well as at art festivals including the Asia Pacific Triennial, the Asian Art Biennale, and the Guangzhou Triennial.